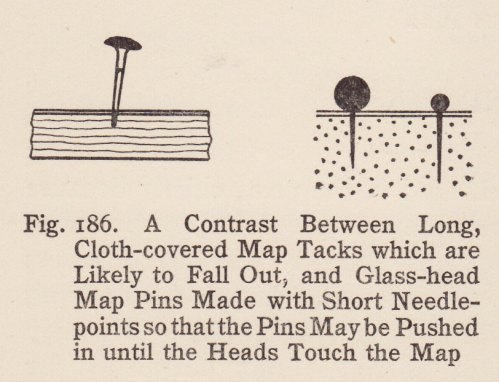

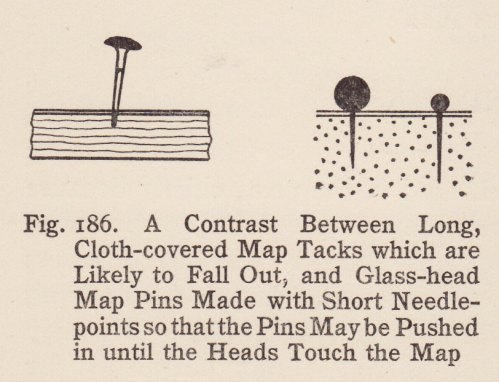

Pin maps have not much been much used in the past, chiefly because a map pin which would give satisfactory service has not been available for common use. Until recently the map markers obtainable have been little more than old-fashioned carpet tacks having chisel-shaped points which cut the surface of any map into which they were pushed. Tacks with rough steel shanks cannot be pushed far into a map if the tacks are to be pulled out again. Also, rough steel is likely to rust so as to cause the whole tack to deteriorate rapidly.

Thus begins a discourse on the map pin – and its brethren map beads, flags, and buttons – by Willard C. Brinton in his Graphic Methods for Presenting Facts (1919). In chapter 12 of that formidable volume, “Maps and Pins,” (2.5mb pdf) we are treated to 27 pages of considered commentary on the map pin: undoubtedly everything that could be said about map pins at the time. May I suggest cartopinography as the appropriate nomenclature for this deliciously narrow subset of the cartographic arts? Yes I may.

The shameful failings of mere tacks as map pins are amply demonstrated in the Brinton screed:

An alternative universe of map pins, beads, flags, and buttons are offered up, and, of course, delightfully illustrated: I repeat the opening image followed by an annotated list of map pin descriptors:

1. Long pin with small size glass head, available in many colors.

2. Long pin of brass wire for use with beads as shown in No.9.

3. Long pin with glass head used in conjunction with a piece of sheet celluloid cut into the shape of a flag.

4. A celluloid flag, with beads above the flag to represent quantity, or beads in different colors to denote various characteristics for the data portrayed. The grip of the sheet celluloid on the pin is sufficient to hold both the beads and the flag at the upper part of the pin.

5. Long pin with large size glass head, obtainable in different colors.

6. Pin like that shown in No.5 used with beads strung upon it.

7. A brass tack large enough to receive gummed labels which may be written upon with a pen.

8. Map pins having sharp points and small spherical glass heads in contact with the map. These pins are available in many different colors; the upper one in No. 8 is red and the lower one blue.

9. Beads in various colors of a size to correspond with the map pins in No. 8. Here the beads were red. White beads, used for every tenth position, show at a glance that there are 22 beads on the pin. Note that the color red photographs as black.

10. Map pins having sharp needle points and spherical glass heads in contact with the map. The pin is of the same general style as No. 8 but it has a head of larger diameter. This pin is obtainable in many colors.

11. Cloth-covered map tacks available in plain colors and in plaids.

12. Single bead used with an ordinary pin as a crude substitute for a regular map pin.

13. Beads in different colors corresponding in size with the map pin of No. 10.

14. Beads of two different sizes representing different things but at the same location.

15. Beads of two different sizes and three different colors. Since both sizes and colors may be varied, and almost any number of beads used on one pin, there are practically unlimited possibilities for the showing of complex data.

16. Beads on a pin which holds down on the map a sheet of colored celluloid cut to the exact shape of a small land area to which attention is directed.

17. A sheet-celluloid marker held by a map pin like that seen in No. 8.

18. Celluloid-covered tack, available in different colors.

19. Celluloid-covered tack with stripes of different colors.

20. Celluloid-covered tack with printed numbers from 1 to 99 inclusive.

21. Celluloid-covered tack having a rough surface so made that the surface may be written upon with pencil or pen, yet erased afterwards or rubbed off with a moist cloth. Lettering may be made permanent by means of a coat of varnish.

22. Large size celluloid-covered tack available in different colors.

23. Large size celluloid-covered tack with stripes of different colors.

24. Very large size celluloid-covered tack.

Included in the study are sundry illustrations of map pinnage at the zenith of development.

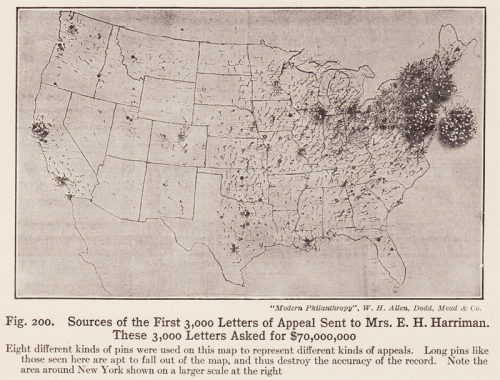

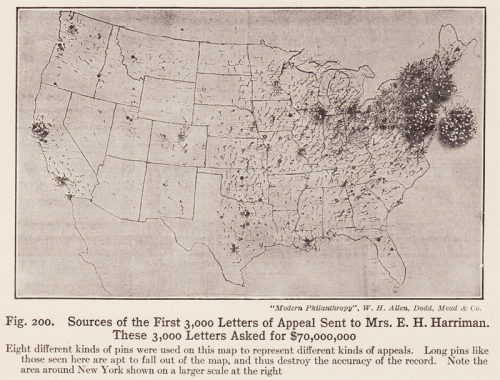

Below find a pin map showing the source of letters appealing for funds from Mary Harriman, the wife of railroad magnate E.H. Harriman. Mrs. Harriman’s fortune was somewhat reduced by the sheer number of map pins acquired for this exercise in cartopinography. Note the excessive pinning of New York City. So many pins are attempting to share the same geography that the map required an additional pin island (floating off the coast of New York city):

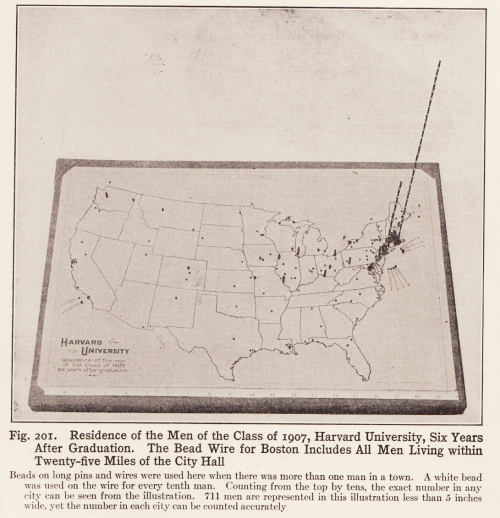

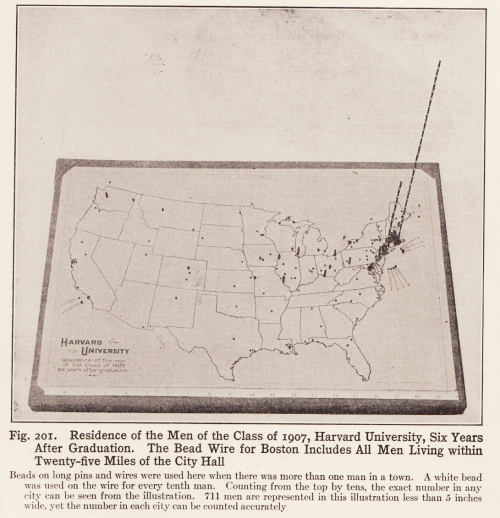

Harvard University, that hotbed of map pin innovation, confronted head-on the “too many pins in one place” problem that plagued the Harriman pin map. Why not, they suggested, create stacks of beads? Why not indeed!

The results, illustrated below, show the residence of 1907 Harvard graduates, six years after graduation. The map beads are stacked on a wire, every 10th bead is white. Why turn to a simple table when you could count beads on wires stuck in a map?

Further pin map considerations must be taken when attempting these protruding pin maps: such a bead map “should be mounted on several layers of corrugated straw-board to allow the long pins to sufficient depth in the mounting to hold fast.” One does not want teetering map pin beads!

The Harvard map sports six layers of straw-board, and a total thickness of 1 and 1/4 inches. Not only does such a sure base support the extensive beadage in the Boston area, but it is also “extremely light and very convenient to handle.”

Yes, I know what you are thinking: what kind of wire would one use for such a map? Would you believe piano wire? But some work is needed to transform piano wire into map bead wire. Brinton details the process: “The piano wire should be heated in a gas flame so as to remove some of the spring temper. After the wire has been heated it can be straightened and it will remain straight without continually springing back into coil form.” Once the heating and straightening has taken place, Brinton suggests a light coating of varnish to stabilize the wire used in longer columns, such as those for Boston and New York City on the map.

I suspect the Harvard map might suffer a bit of map bead flaccidity if hung upon a wall, given gravity and all. I also wonder about the hazards of such lengthy map beadings: a farsighted passer-by might, for example, receive a nasty map bead wire puncture-wound upon viewing the map too closely. No such injuries were reported in Brinton’s tome, however.

In our modern age of fancy maps-on-the-web the tangible map pin is certainly in decline. Yet a quick search leads to several suppliers of map pins, flags, and similar items, such as the Hudson Map company and The Map Shop.

Yet it is the ubiquitous Google Map that has saved the map pin from obscurity. Google’s default map pin marker can certainly be replaced by any kind of marker you want (see Custom Map Symbols in Google Maps) but who wants to futz around with that?

The Google Map map pin has taken its place as a literal pop-culture icon. Indeed, Google’s digital map pin has leaked back into earthly reality. Below find the work of map pin artist Adam Bartholl:

The map pin is dead! Long live the map pin!

Read Full Post »