Céline Boyer: Empreintes (from Céline Boyer)

•••••••

Denis Wood’s 2010 book Rethinking the Power of Maps includes a discussion of exhibits devoted to maps created by artists prior to 2010. A significant number of exhibits have opened since the book was published. Map Art Exhibitions, 2010-11 was posted in late 2012, and an update for 2012-13 is below.

Map Art Exhibitions, 2012-13

While we know there were more exhibitions than we cover here – so please note any we’ve overlooked in the comments – the last two years have marked a slackening of interest in map art as the genre is increasingly taken for granted. Map art is gradually seeping into art the way landscape painting did into the Western tradition in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, solidifying its position in the world of art as it loses its novelty.

Zarina: Dividing Line (Paper Like Skin, Guggenheim)

One thing this means is that map art is beginning to show up in broader bodies of work – as in Zarina Hasmi’s (above) or Erik Parker’s (below) – and in exhibitions on other themes – as in three of shows we’ve included here.

Eric Parker: Preoccupied (Too Mad to be Scared: Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum)

•••••••

Julia Penrose: from Mapping the Future: Where Are You Now?

Mapping The Future: Where Are You Now? Textile Forum South West, Gallery at The Brewhouse Theatre & Arts Centre, Taunton, England, 2012. Following a successful Textiles Forum South West (TFSW) conference, Maps define the future: where are you now? held at Somerset College in 2011, our exhibition here included the work of 35 textile artists reflecting on a variety of map themes. The artists utilized a range of experimental techniques, including delicate hand stitch, felt making, quilting, collage knitting, sculpture as well as digital media. Reviews of the show are posted at the exhibition site, along with descriptions of all the projects. There’s a catalogue too, as well as a DVD of the show.

•••••••

Joyce Kozloff: JEEZ (Joyce Kozloff)

Joyce Kozloff: JEEZ, The Armory Show Modern, New York, 2012. About JEEZ, which hung at the main entrance of the 2012 Armory Show Modern in New York, Kozloff has said, “JEEZ is my election year piece, a 12’ x 12’ painting based on the Ebstorf map, a 13th century mappa mundi, which depicted Biblical stories and pagan myths within the world as it was then known, with Christ’s body as a symbolic and literal frame. I have inserted and rendered 125 images of Jesus from the history of art and worldwide popular culture – black, Latino, female, Asian; adults and babies; gay and straight; images from the movies and New Age hippies off the Internet – each true to its artistic ideal. As the archetypes and stereotypes accumulate, holy portraits are transformed into a rogue’s gallery of mismatched characters. Seen altogether, this proliferation wryly erodes their power.” Kozloff’s work was also included in a number of the other exhibitions noted here, in exhibitions at D. C. Moore in New York, and elsewhere.

•••••••

from Atlas Critique

Atlas critique, Parc Saint Léger, Contemporary Art Centre, Pougues-les-Eaux, France, 2012. The curators of this very interesting show wrote: “Although we are aware of the extent to which cartography as a discipline has been profoundly imbricated in the performative production of the narratives of modernity, in objective and positivist rationality, but also the history of colonialism and nationalistic constructions, for artists today, it has become a privileged site for the invention of counter-practices that open up new perspectives and participate in a deconstruction of hegemonies and post-colonial epistemologies as alternative tools for the production of knowledges, narratives and realities.” In demonstration of this they showed the work of, Francis Alÿs, Erick Beltrán, Berger & Berger, Border Art Workshop [a San Diego-based collaborative], Mark Boulos, Lewis Carroll / Henry Holiday, Chto delat? [a Russian art collective], Fernand Deligny, Michael Druks, Claire Fontaine, Internacional Errorista [an international art movement], Pedro Lasch, Vincent Meessen, Nástio Mosquito, Estefanía Peñafiel Loaiza, Lia Perjovschi, Radek Community+Dmitri Gutov [Moscow-based group], Philippe Rekacewicz, R.E.P. Group [a Ukrainian art collective], Allan Sekula & Noël Burch, Société Réaliste [a Parisian cooperative], Stalker [a walking group based in Rome], Endre Tót, David Wojnarowicz / James Wentzy / AIDS Community Television. This was an amazing exhibition, accompanied by conferences, performances, and films.

•••••••

Richard Long: A Line Made by Walking (from Contemporary Cartographies: Drawing Thought)

Contemporary Cartographies: Drawing Thought, CaixaForum, Barcelona, Spain, 2012. Curated by Helena Tatay, this important exhibition included more than 140 works by 77 artists, from the classics (Dalí, Debord, Duchamp) to the contemporary (Alÿs, Kentridge, Kuitca), with the goal of “inviting the visitor to question both the systems of representation that we use and the ideas that underpin them.” As the press release put it, “The central aim of this exhibition is, therefore, to explore the ways in which contemporary artists have used cartographic language to subvert traditional systems of representation, propose new formulas or suggest the very impossibility of representing a globalised, ever more chaotic world.”

•••••••

Joyce Kozloff: Targets (from The Map as Art, Kemper Museum)

The Map as Art, Kemper Museum. St. Louis, Missouri, 2013. Inspired by Katharine Harmon’s best-selling book, The Map as Art, this exhibition presented work that explored the issue of mapping – whether conceptually or quite literally – while examining systems of personal gesture involved in large-scale works. The exhibition featured more than 30 works by seven artists: Ingrid Calame, Nathan Carter, Tiffany Chung, Joyce Kozloff, Lordy Rodriguez, Robert Walden, and Heidi Whitman, several of whom made presentations in the extensive programming that accompanied the show. It was co-curated by Kemper Museum curator Barbara O’Brien and Katharine Harmon. There was an illustrated gallery card. Sept 14, 2012-April 21, 2013.

•••••••

David Reimondo: Patch World Inverso (from MAPPAMUNDI, art et cartography)

MAPPAMUNDI, art et cartographie, Hôtel des Arts, Centre d’art du Conseil général du Var, Toulon, 2013. Less pretentious than some shows, but more exciting, MAPPAMUNDI brought together 58 works by 26 artists, a number of them represented in Atlas critique (for example, Stalker) and/or Contemporary Cartographies: Drawing Thought (for example, Kuitca) in a show organized by Guillaume Monsaingeon around three themes: the body, combat, and the tale. Monsaingeon also wrote the fully-illustrated, 190-page catalogue, MAPPAMUNDI, art et cartographie, which opens with a long history of maps and map art. The exhibition included Céline Boyer’s project Empreintes, a collection of photographs of hands, against black backgrounds, on which maps of their places of origin (Senegal, Iran, Spain, and so on) have been superimposed. A 100-page book – all of which fold out – documents Empreintes. Boyer’s project is connected to those in the exhibition of Qin Ga and Kuitca, though indeed this show was rich in resonances.

•••••••

Expanded Map (from Expanded Map)

Expanded Map, RM Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand, 2013. Curated by Ruth Watson and James Wylie, who both co-authored the catalogue and have pieces in the show, Expanded Map is an artists show in an artists space. With the exception of Gigi Scaria, Lize Mogel, and Clare Noonan all the artists are locals: Auckland has a rich map art scene! The show was divided into two parts, both of them covered in the color catalogue.

•••••••

Mark Schatz: Universe Hive (From ArtHopper.com)

Universe, The Sculpture Center, Cleveland, Ohio, 2013. Mark Schatz mapped the world in this sprawling, double-sided landscape model built with ideas from architects, planners, hobbyists, and self-taught artists,. The faceted map could be folded up to make a Buckminster Fuller-inspired cuboctohedron; and it drew attention to individual perceptions of ones place, ones residence or “home,” and how it’s all a multifaceted, living, growing experience.

•••••••

Samuel Rowlett, Still From “Landscape Painting in the Expanded Field” (from Artfcity.com)

Artists’ Walks: The Persistence of Peripateticism, Dorsky Gallery, New York, 2013. Curated by Earl Miller, this is an example of a show tangential to the world of map art, but in an essential way, for walking, after all was for most of human history how we came to know the world. A lot of peripatetic art still uses maps to document the walks. Here this was the case for the work of Danica Phelps, Gwen MacGregor, and Sandra Rechico. The latter two also organized a piece, “Map It Out (New York),” in which they invited people to map the travels they’d made during the day, and then they assembled the collected drawings into a psychogeographic portrait of New York that hung alongside works by Richard Long, Hamish Fulton, and others. Neat show.

•••••••

Joseph Kosuth: From Memory, Draw a Map of the United States (from Huffington Post)

From Memory: Draw a Map of the United States, Sean Kelly Gallery, New York, 2013. This show is the first presentation of a project conceived and produced in 1971-1972 by Hisachika Takahashi. Takahashi, a Japanese artist living in New York, asked twenty-two fellow artists to each draw or paint a map of the United States entirely from memory on the handmade Japanese paper he provided: Arakawa, Jed Bark, Mel Bochner, Juan Downey, Alex Hay, Jasper Johns, Joseph Kosuth, Jeffrey Lew, Jane Logemann, Brice Marden, Gordon Matta-Clark, Richard Nonas, Robert Petersen, Robert Rauschenberg, Dorothea Rockburne, James Rosenquist, Keith Sonnier, Hisachika Takahashi, Cy Twombly, Susan Weil, Lawrence Weiner, Robert Whitman and Don Wyman. It’s a valuable document of the scene and of the map ferment beginning to grip the art world.

•••••••

Detail from Nalini Malani and Iftikhar Dadi: Bloodlines (from IndiWeek)

Lines of Control: Partition as a Productive Space, Nasher Museum of Art, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, 2013-14. This is another show at once tangential to map art and yet concerned with an essential map element: lines of control. The lines of control in this case are mostly borders through contested areas (India/Pakistan, Israel/Palestine, Mexico/US, and so on). Green Cardamom brought together more than thirty contemporary artists (from Francis Alÿs to Muhammad Zeeshan) and a host of other contributors (including Iftikhar Dadi and Irit Rogoff) to mount a ceaselessly stimulating exhibition, first in 2012 at Cornell and then in 2013-14 at Duke. It spawned a 240-page full-color catalogue. A great stimulating show and a terrific catalogue!

•••••••

Maya Lin: Blue Lake Pass (from IndiWeek)

Surveying the Terrain, Contemporary Art Museum, Raleigh, 2013-14. While Lines of Control was up at Duke in Durham, across the Triangle in Raleigh, CAM was showing Surveying the Terrain, another show tangential to map art, yet equally concerned with an essential subject; or, as the gallery brochure put it, “Surveying the Terrain explores contemporary artworks that map our terrain.” Curated by Dan Solomon, it featured ten artists including Alfredo Jaar, Laura Kurgan, Maya Lin, and Trevor Paglen. Beautiful work!

•••••••

(from Bronx River Art)

MAPnificent! Artists Use Maps, Bronx River Art Center, New York, 2013-14. Curated by Yulia Tikhonova, this show’s 18 artists – among whom were Paula Scher and Mannahatta – approached the map from every direction. This may have been the year’s most classic map art show, a fading form.

•••••••

Roosmarijn Pallandt (from Roosmarijnpallandt.com)

Unmapping the World, EXD’13 / Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical, Palácio dos Condes da Calheta, Lisbon, Portugal, 2013. Part of Experimental International Design Biennial 2013, and curated by Annelids de Vet (of the Subjective Atlas of … fame) and Nuno Coelho, the exhibit was “an exploration into the field of reactive map making practices. It aims to counterpoise the apparent neutrality of professional cartography through contemporary engaged mapping projects. In this exhibition, ways of mapping are used to resist the authority of state, to question ruling power structures and to expose the propensity of maps to simplify our world. The act of uncapping is presented as a poetic form of resistance.” And so much more!

•••••••

Across the Wall: Israeli Settlement Bus Routes: Ahmad Barclay & Polypod (from Visualizing Palestine)

The Cartography of the Unseen, The Research Gallery, Holon Institute of Technology, Holon, Israel, 2013. This exhibition dealt with “the political reading of the overt and covert mechanisms embedded in the act of cartography, by exposing the ideological aspects, as well as the solicitation to action performed through mapping. The exhibition analyses the ways in which the design of maps conditions the very interpretation of them, and examines how the act of mapping affects the reorganization of the mapped territory.” Thirteen projects from as many territories were presented, including work from both Israel and Palestine. Radical presentation!

•••••••

Read Full Post »

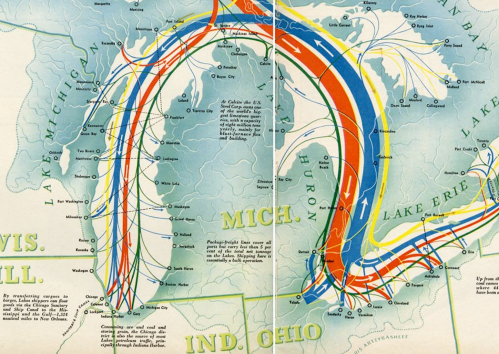

Back when Denis Wood and I were planning the 3rd edition of Making Maps, I stumbled upon a map of world tropical diseases Boris Artzybasheff created for Life Magazine (“World Map of the Major Tropical Diseases,” Life Magazine, May 1, 1944; high-resolution

Back when Denis Wood and I were planning the 3rd edition of Making Maps, I stumbled upon a map of world tropical diseases Boris Artzybasheff created for Life Magazine (“World Map of the Major Tropical Diseases,” Life Magazine, May 1, 1944; high-resolution

“In the late 1930s and early 1940s Artzybasheff began illustrating articles for Fortune and other popular magazines, usually with vividly drawn graphic renditions of maps or other informational diagrams. In the September, 1940 issue of Fortune magazine, for example, Artzybasheff provided a striking and colorful illustration for an article on how military pilots experience oxygen deficiencies and aeroembolism (decompression sickness or temporary blackouts attributed to nitrogen bubbles that form in the spinal fluid) when ascending rapidly to heights of 30,000 feet.” (Williams, 2007, p. 126). Diagram (left): “A Pilot’s Blackout,” from “Selection of Military Pilots: Not Every Flyer is Fit for Combat,” Fortune, September 1940, p. 81.

“In the late 1930s and early 1940s Artzybasheff began illustrating articles for Fortune and other popular magazines, usually with vividly drawn graphic renditions of maps or other informational diagrams. In the September, 1940 issue of Fortune magazine, for example, Artzybasheff provided a striking and colorful illustration for an article on how military pilots experience oxygen deficiencies and aeroembolism (decompression sickness or temporary blackouts attributed to nitrogen bubbles that form in the spinal fluid) when ascending rapidly to heights of 30,000 feet.” (Williams, 2007, p. 126). Diagram (left): “A Pilot’s Blackout,” from “Selection of Military Pilots: Not Every Flyer is Fit for Combat,” Fortune, September 1940, p. 81.

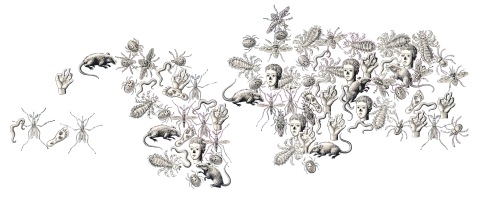

“In a 1942 letter to Artzybasheff, Boggs asks if the artist could potentially draw the head of a man on a white billiard ball, in hopes of designing a model that could show how projecting global features creates significant distortions on a flat map—in other words, flattening the nations and populations of the world is much like flattening a person’s face beyond all recognition. As he points out to Artzybasheff, ‘What I would like to get across to the ‘flat-mappers’ is that when we are looking at a flat map which includes the whole world, we are looking at a caricature which is analogous to representing the face, both sides of the head, back and top of the head, and beneath the chin all on one flat surface.” (Barney, 2011, p. 189)

“In a 1942 letter to Artzybasheff, Boggs asks if the artist could potentially draw the head of a man on a white billiard ball, in hopes of designing a model that could show how projecting global features creates significant distortions on a flat map—in other words, flattening the nations and populations of the world is much like flattening a person’s face beyond all recognition. As he points out to Artzybasheff, ‘What I would like to get across to the ‘flat-mappers’ is that when we are looking at a flat map which includes the whole world, we are looking at a caricature which is analogous to representing the face, both sides of the head, back and top of the head, and beneath the chin all on one flat surface.” (Barney, 2011, p. 189)