|  |  |

Three terrific new books on maps and mapping…

Review by Denis Wood

Linda Campbell, Andrew Newman, Sara Safransky, and Tim Stallman, eds., A People’s Atlas of Detroit (Wayne State University Press, Detroit, 2020).

Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren Klein. Data Feminism (MIT Press, Cambridge, 2020).

Rasmus Grønfeldt Winther. When Maps Become the World (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2020).

I read these three books in order, one after the other, with ever increasing pleasure. A Blacks’ atlas of Detroit, two women writing about data from a feminist perspective, a philosopher of science using “map thinking” to mull over everything from geodetic surveys to genetics – these books could have been deadly, a sure prescription for eyes glazed-over as the books slipped from my fingers to the floor. Instead: great interest, continuous surprises, and mounting satisfaction.

Reading about Detroit made me think about growing up in Cleveland. Cleveland was an exciting place to live in the 1940s and 1950s. Its Terminal Tower was the tallest building in the world (outside of New York). In 1946 George Szell began conducting its symphony and in 1948 the Indians won the World Series. Thousands worked in the city’s steel mills. It had a fabulous streetcar system. Walking down Euclid Avenue in those days was like walking down Fifth Avenue in New York, just that crowded and exciting. Forty years later, in the middle of the afternoon, I lay down in the middle of Euclid Avenue and had to wait four minutes before a car came along to honk me out of the way. The place was a desert. When I was growing up Cleveland was the seventh largest city in the US. It’s the 53rd now and it feels it. It’s shrunken. It’s had its guts ripped out of it.

Back in those days Detroit was the fifth largest city in the US. It was Motor City, where the cars came from and, soon enough, Motown where the songs came from. Detroit’s fall was like Cleveland’s, though if you believed what you read it was actually much, much worse. Unlike Cleveland, Detroit was always in the news. Its miles of deserted, flattened blocks became notorious. The city went bankrupt, and it was taken over by a state-imposed manager. He wanted to sell the paintings out of the art museum! The place was an unmitigated disaster. Reading this stuff you’d never believe that Detroit, with its 670,000 inhabitants, is still the 23rd largest city in the US, that Metro Detroit with its 4.3 million inhabitants is the nation’s fourteenth, or that the art museum with its 677,000 annual visitors is among the most visited in the world. That is, you’d never believe that rather than a horrifying wasteland, Detroit’s an exciting, a vibrant place to live, maybe especially for the Blacks who man (and woman!) the front lines of a fierce struggle against racism, revanchism, and capitalism. This struggle is the subject of A People’s Atlas of Detroit.

The book’s introduction clarifies what it means by “people’s” and “atlas”. Not an atlas of all the peoples of Detroit – an atlas of Detroit – the book’s a collection of texts and maps (there are nearly four dozen of these) that illuminates a moment in the struggle of Black Detroiters for their city; and although it was published in 2020, that moment was essentially 2012 when most of the interviews here were collected. Laid out in six chapters, their titles capture the book’s contents: “Detroit and the Long Struggle for Liberation,” “This Land is Ours: Toward a New Urban Commons,” “Growing a Revolution,” “Suspending Democracy Is Violence,” “Gentrification Is Only Part of It: Understanding Race and Displacement in Detroit,” and “The Right to the City.” Each of these runs to some fifty pages of maps but, mostly, texts, texts drawn from the people the book’s about.

Take Grace Lee Boggs and Sterling Toles who have a conversation at the end of the first chapter. Grace Lee, the daughter of Chinese immigrants, married the Alabama-born African-American and Chrysler auto worker, James Boggs, in 1953, and in 1974 these two activists and “fiercely independent intellectuals” published Revolution and Evolution in the Twentieth Century which, still very much in print (along with the rest of their work), remains a key text for radical thinking. Toles, on the other hand, is “an illustrator, sound sculptor, DJ and music producer” who runs a recording studio out of his home. While you might imagine that Toles would be interviewing Boggs, it turns out to be the other way around, Boggs probing Toles about his work with the local kids who’d been censored at other studios: “My whole thing was, I wouldn’t censor them, but I would ask them why they felt what they felt. One of the premises that I really work on is that so much of this culture is about conduct, control, and behavior control as opposed to nourishment,” which leads into talk about “nurturing.” After James Boggs died, in 1993, the James and Grace Lee Boggs Center to Nurture Community Leadership was founded, and “nurture” turns out to be a theme that that runs throughout A People’s Atlas of Detroit.

The whole book’s like this, insanely dense. Take the cover. While a piece of a street map fills the sky, otherwise the cover’s a photo of two Black kids walking down a street away from the camera. On the left Crocketts Groceries sells beer and wine. On the right a chain-link fence topped with barbed wire encloses a yard. If you look closely you can see in the distance that the street’s been closed off since, as a note on the back cover makes clear, the photo was taken at “Yusef Shakur’s twelfth annual backpack giveaway and neighborhood festival,” which explains the kids’ shiny new backpacks. Now, I rarely expect book covers to have much to do with the book. Usually they’re designed after the book’s on its way to the press, by a designer who may have only the sketchiest idea of its contents. So it was shock to come across, on page 293, in the introduction to Yusef “Bunchy” Shakur’s “Reclaiming Our Souls,” that Shakur’s coffee shop “is a community space that offers a public computer station, features local art, hosts poetry readings, and organizes an annual back-to-school backpack drive, which is featured on the cover of this book.” I mean, this almost never happens.

But then the whole book’s terrific, building smoothly to the cymbal crash of the concluding chapter, “The Right to the City,” where interviews are presented on the rights to water, to environmental justice, to mobility, to education, and to freedom from crime and police harassment, in each case examining situations in which these rights have been or are denied: the notorious water shutoffs; the serious perils of pollution, with a focus on the city’s incinerator; the problems stemming from the city’s fragmented transit systems; the school closures; and the impact of the city’s insane rates of incarceration. In each case solutions are advanced whereby Detroiters have or are reclaiming these rights, in the process reclaiming, as “Bunchy” Shakur puts it, “our souls.” It’s inspiring, but it’s also a mind-boggling amount of work, work Black Detroiters have embraced. That’s what’s really inspiring!

Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren Klein’s Data Feminism is a whole different kettle of fish. A book by two feminist academics explaining why data science needs feminism, it would be hard to imagine anything further from A People’s Atlas of Detroit; and yet it’s animated by a similar spirit of defiant resistance, and it shares with the atlas a determined resolution to address the problems it identifies. These are laid out in seven chapters that follow a welcoming and incisive introduction, and again their titles neatly capture the book’s contents: “The Power Chapter,” “Collect, Analyze, Imagine, Teach,” “ On Rational, Scientific, Objective Viewpoints from Mythical, Imaginary Impossible Standpoints,” “What Gets Counted Counts,” “Unicorns, Janitors, Ninjas, Wizards, and Rock Stars,” “The Numbers Don’t Speak for Themselves,” and “Show Your Work.” An active principle, effectively a subtitle, interpret these: “Examine Power,” “Challenge Power,” “Elevate Emotion and Embodiment,” “Rethink Binaries and Hierarchies,” “Embrace Pluralism,” “Consider Context,” and “Make Labor Visible.”

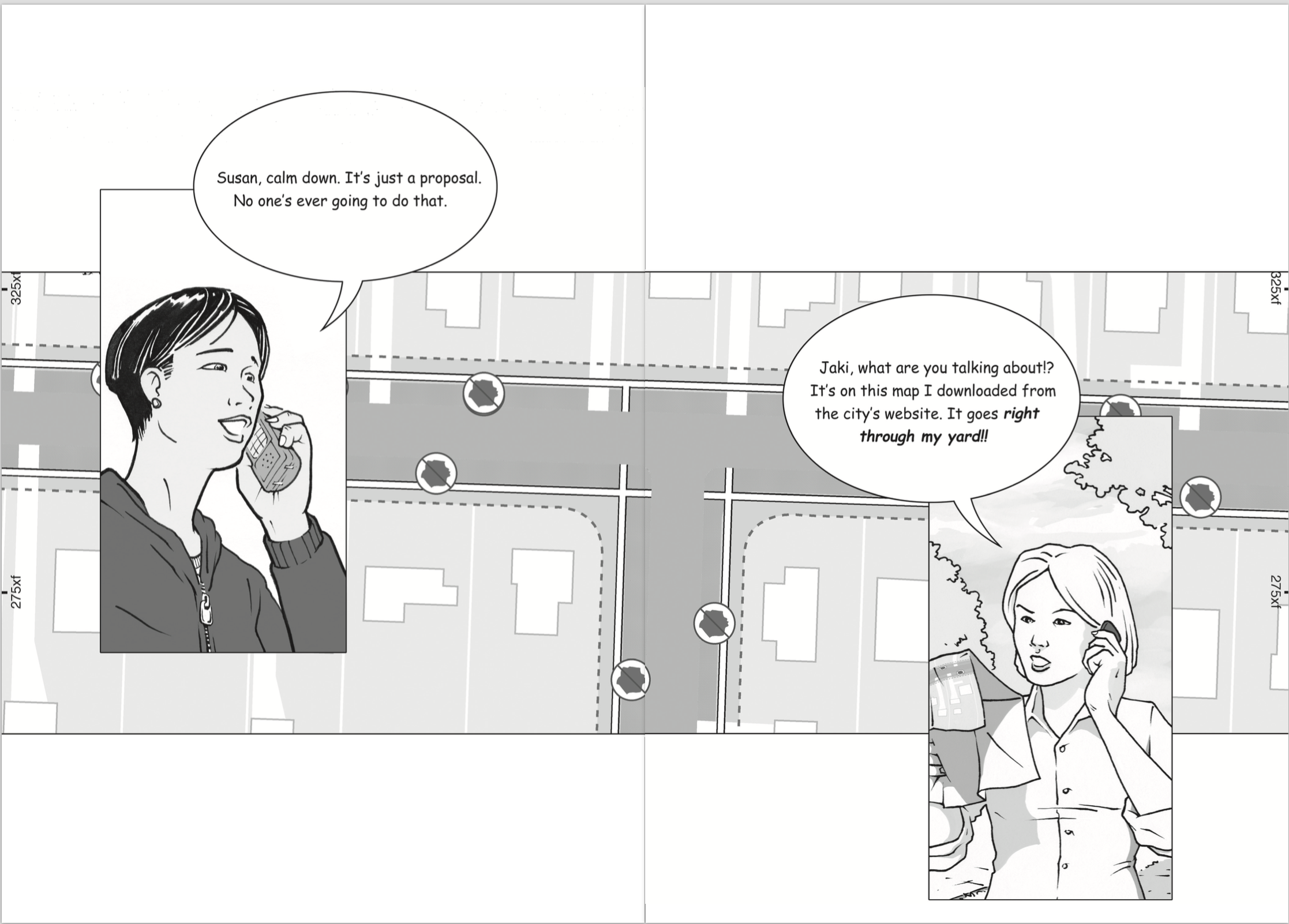

Each subtitle is then further spelled out in an attached sentence. For example, “Challenge Power,” is followed by “Data Feminism commits to challenging unequal power structures and working toward justice.” This chapter opens with a comparison of the Detroit Geographical Expedition and Institute’s map, Where Commuters Run Over Black Children on the Pointes-Downtown Track, with the Detroit Board of Commerce’s Residential Security Map. The first was made by a collaboration between young Black adults and white academics from local universities, while the second was made by white men collaborating with the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, producing – to cut to the chase – a map of Detroit neighborhoods on which the Black neighborhoods appear in red. This 1939 map is an early instance of what became known as “redlining” maps, denying to most of those who lived within the red borders the ability to borrow money to buy a home. D’Ignazio and Klein compare these redlining maps to the way big data are fetishized today – as rational, scientific, and objective – where what is overlooked is the unequal power structures that underlie and dictate the character of the rational, scientific, and objective data used. In the redlining maps, that character was all about protecting and preserving home ownership as a way of accumulating wealth and power for whites. D’Ignazio and Klein contrast this data with the data underlying the Run Over Black Children map which, previously unavailable, had to be collected from the police (with no little effort), and then compiled and plotted by the young Blacks who lived in the community itself. A sharper example of a challenge to power working toward justice would be hard to imagine.

Each chapter opens with a similarly compelling example, and then proceeds to think through the issues raised, typically through further examples, before closing with another, equally compelling example. In the power chapter the concluding example arises out of an idea called “mathematics for spatial justice,” specifically from a project, Local Lotto, that unfolded in the Bronx. Local Lotto grounded the teaching of statistics and data collection in contexts of equity, specifically the question whether the New York state lottery was good or bad for the neighborhood. The students learned about statistics and data analysis, roamed the neighborhood to collect their data, analyzed it, and gave presentations to each other. Finally they created “a data-driven argument: an opinion piece supported with evidence from their statistical and spatial analyses, as well as their fieldwork.” Again, the challenge to power is in your face and, like so many of the rest of the projects in the book, it’s rich, detailed, many-layered and multi-stranded.

Organizing the book’s arguments is what sociologist Patricia Hill Collins calls “the matrix of domination,” a construct she uses to explain how systems of power are configured and experienced. Her matrix embraces four domains – law and policies; their enforcement; culture and media; and individual experiences of oppression – which D’Ignazio and Klein return to again and again, as in … the question of pocket sizes. Here the larger issue is classification systems, specifically “how race, gender, and class (among other things) intersect to enhance opportunities for some people and constrain opportunities for others.” The examples D’Ignazio and Klein deploy make it clear the the forces operating through the matrix of domination are “sneaky and diffuse”: here, for instance, women’s pants pockets are almost half as long as those for men (that is, they’re too small for a smartphone). Of course this has a history, and it’s one in which the matrix of domination plays a role again and again, and so this difference in pocket sizes leads into a discussion of gender, especially the gender binary, which leads to the issue of binaries in general, which is a big player in what gets counted. That is, binaries are a big constraint on what gets counted.

The example that opens the fifth chapter is San Francisco’s Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, exhibiting (among other things) how “partiality and contestation” can take place in graphical design, thereby upholding the fourth principle of data feminism: the embrace of pluralism. Constructively, this builds on the previous chapter’s dismay over the constraints of binaries, here expanded to a polemic against the cleansing and tidying to which datasets are regularly subjected in order to make them amenable to … well, to simple “yes” or “no” outcomes for what are immensely complicated public debates. As D’Ignazio and Klein conclude the chapter: “embracing pluralism is a feminist strategy for mitigating this risk. It allows both time and space for a range of participants to contribute their knowledge of a data project and to do so at all stages of that project.”

But what’s really great about this book is the way it practices what it preaches. When you reach the end of the text, you don’t reach the end of the book. Instead it continues for another ninety-nine pages, half again as long as the text itself. These open with “Our Values and Our Metrics for Holding Ourselves Accountable,” which opens with an historical note that in turn opens with an allusion to the “open peer review process” that took place online. Okay, that’s unusual enough, but it then proceeds to list their key values: intersectionality, equity, proximity, the humanity of data, reflexivity, transparency, accountability and positionality. As they say, legitimate knowledge “has a race and a gender, as well as a class and geographic location,” concluding that “values are not enough. We have to put those values into action and hold ourselves accountable again and again.” Therefore this section is followed by Isabel Carter’s “Auditing Data Feminism,” which explains how the audit, included in the previous section, was carried out.

After this come “Acknowledgment of Community Organizations,” describing the two organizations to which a portion of the royalties from Data Feminism have been redirected; and, then, detailed “Figure Credits,” sixty-six pages of notes, a name index, and a subject index. And these are some notes. Not your common citations, these are discursive and enriching, expanding the text in the valuable directions. These are notes you don’t mind flipping to the back to read because the content warrants the disruption, or rather the extension, because that’s what they do, they extend the arguments of the text. Footnotes to the redlining text, for example, expand on the way the tactic is still used to deny housing to Blacks, citing among many other cases the one brought in 2018 against Facebook by the Department of Housing and Urban Development for enabling discriminatory advertising by housing providers. At the same time they expanded on the way Gwendolyn Warren’s work on the Run Over Black Children map has been so often misattributed to Bill Bunge (by me among others).

No, this is a good book, meriting a very careful read.

When Maps Become the World, by Rasmus Grønfeldt Winther, demands a very careful read, if only to to keep up with the arguments, which are many, mutually-referencing, and continually compounding. Winther is a philosopher of science and this is straight-up philosophy of science. In fact his central thesis is “that science is an overarching mapping project of the world,” a thesis that more than justifies the four-chapter-long explication of what he calls “map-thinking.” “Map thinking,” says Winther, “refers to philosophical reflection concerning what maps are and how they are made and used,” where “philosophical reflection” is precisely that, reflection. But … philosophical reflection: “Map thinking massages the imagination; excavates hidden assumptions; challenges and synthesizes dualisms; and invites us to reflect on space and time – including the future.” This should make plain that When Maps Become the World is discursive, which means, as Merriam-Webster confirms, that it’s: “marked by a method of resolving complex expressions into simpler or more basic ones: marked by analytical reasoning.”

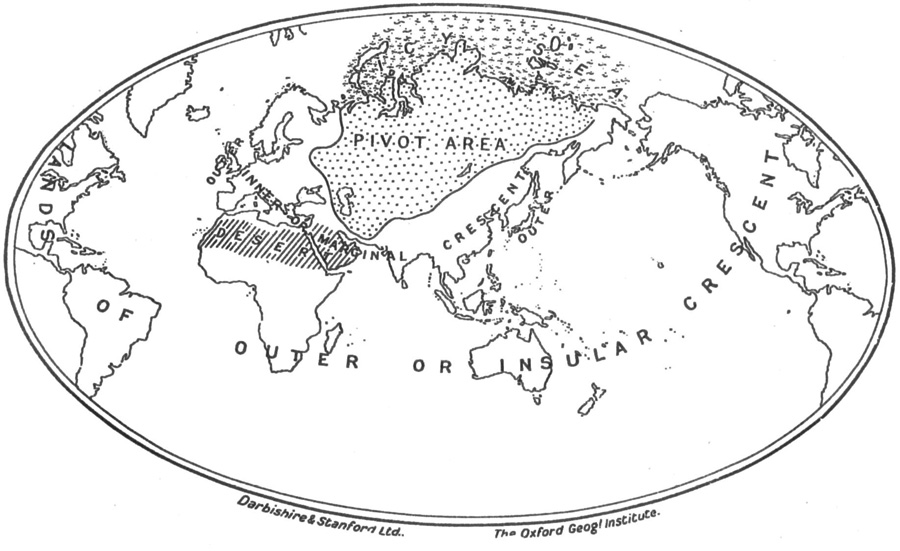

Here the complex expression is “map thinking” and the simpler or more basic things into which it’s resolved include: eight map analogies (e.g., “A scientific theory is a map of the world”), assumption archeology, an abstraction-ontologizing account, partitioning frames, pernicious reification, contextual objectivity with its integration platform, and a multiple representations account. Each of these is in turn resolved into similarly simpler parts, as in the multiple representations account getting thought through ontologizing, merely-seeing-as, and pluralistic ontologizing. Here ontologizing is said to occur “when an individual takes the internal world of a map or scientific representation to really be the world it intends to represent.” In contrast, when merely-seeing-as, a user “comprehends that the content of the map, model, or theory is one limited way of viewing, and acting, in the world.” We’re said to be pluralistically ontologizing when we “communally, deliberately, and mindfully respect multiple representations,” including those unfamiliar or taken-for-granted.

Ontologizing, merely-seeing-as, and pluralistic ontologizing amount to three different postures that can be taken with respect to existence. For example, the ontologist who has grown up with the Mercator projection alone may be inclined to believe Greenland is about the size of Africa, whereas Africa is actually fourteen times the size of Greenland. One who merely-sees-as understands there are other ways to see the world: for example, that offered by the Gall-Peters projection which, while it does show things in their true sizes does not, as does the Mercator, show them in their true shapes. A pluralistic ontologist understands that there are more ways to think about the world than you can squeeze onto a projection, and opens him- or herself up to wholly other world views, ancient, anthropological, or just plain loony (like most contemporary flat-earth apostles). In another domain, Galen’s humoral theory explained disease as an imbalance of the humors. Long and widely ontologized in the West, in the later nineteenth century humoral theory was forced to compete with the then new germ theory of Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch, after which this became, well, the world. Today germ theory is merely-seen-as the explanation for most diseases, dominantly in our age of the coronavirus, but more pluralistic ontologists understand that illness can have many causes, viruses and bacteria, but also radiation and lead poisoning, nutritional deficiencies, stress, and so on.

Maps become the world when either literal maps or scientific theories get mistaken for the world, foreclosing alternatives. Maps like these lurk behind phrases like, “It’s hard to imagine but people used to believe …” before the unfolding of alternative, typically “old-fashioned” views, like that of a flat earth (now spherical), or those with the earth in the center of the universe (which is now at the edge of a minor galaxy), or the one in which ice, water, and steam were different substances (whereas today they’re different phases of a common substance), or that in which different “races” were all but different species (which today are non-existent), or that of the earth without plate tectonics. I grew up in that one, with geologists teaching me geosynclinal theory and making fun of “this plate-tectonic nonsense” which, of course, today is … the world.

Having laid out this way of thinking about the world, with its pernicious reification and contextual objectivity, Winther applies it to science to show it in action, that is, to sciences, since When Maps Become the World takes on no fewer than eight of them. Naturally he starts with the universe which naturally he begins with the Big Bang. Here we begin with the cosmic microwave background map, of the universe shortly after its birth. Winther contrasts this with the map of the current universe created by Margaret Geller and associates in 1977, or at least with the positions of a thousand of its galaxies. Finally Wither turns to the more recent three-dimensional maps of galactic motion, of Hélene Courtois, R. Brent Tully and their team, which track the motions of hundreds of thousands of galaxies. Winther takes this as an opportunity to review his abstraction-ontologizing account with its complicated problems of the calibration of cosmic distances, the collection and management of cosmological data, and their generalization into extreme space maps.

Next he drops his gaze to the earth where, with conventionally scaled geologic mapping, he traces the history and state of plate tectonics; before freaking out with state-space maps in physics and physical chemistry (also known as phase diagrams). Finally he considers analogous maps in mathematics where we not only consider mathematical mappings but the literal cartography of the great German mathematician, Carl Friedrich Gauss, work that through his student Bernhard Riemann’s work on manifolds underwrites all of twentieth century physics. It’s all space and time – Winther makes that case convincingly – and so all this can be thought through the lens of map thinking quite easily.

This proves no less true of the examples in the following chapter where Winther emphasizes the importance of assumption archeology and the power of countermapping. Here he’s tackling our mapping of ourselves: migration mapping, brain mapping, and statistical causal mapping. He opens with the abstractive-averaging assumptions so common under maps of migration, tracing these through the work of Ernst Ravenstein, Waldo Tobler and others. These he counters with, for example, the migrant death mapping of Humane Borders/Fronteras Compasivas; and with the mapping of Tunisian migration by Robby Habans for the Spaces in Migration project of Martina Tazzioli and colleagues. Both of these radically resist the abstractive-averaging assumptions of “mainstream” migration mapping. Winther explores brain mapping the same way, a tour through decompositional assumptions, phrenological maps, and the somatosensory and motor homunculi being followed by the countermaps of Russell Poldrack and Michael Anderson, namely, cognitive ontologies and functional fingerprints. The path diagrams of statistical causal maps get countered by Eric Turkheimer and Helen Longino’s doubts about the utility of the whole approach, opening questions about, for example, the very possibility of decomposing the statistical interactions into the individual behaviors of the interacting individuals, and so asking: what’s being explained?

In his final science chapter Winther turns to genetics (the subject of his forthcoming book), to look at seven genetic maps, integrating them into a paradigmatic integration platform on which he notes each map’s genetic type, its partitioning frame, its space and time frames, and its map type. Take the linear genetic map. Its partitioning frame features morphological character, chromosome bands and nucleotides in chromosomal and nucleotide space in the time that a crossover takes in a germ cell. It’s an extreme-scale map. In contrast the literal genetic map partitions the domain into genes and their relevant geographic regions in geographic space and evolutionary time. It’s a literal geographic map. There’s lots more, some of it completely abstract (the adaptive landscape, for instance). The last chapter embeds all of this, and the seven previous chapters, into the philosophy of science, concluding with an invitation to dream. I think it’s safe to say that the book ends on a high …

It’s only three-hundred pages but When Maps Become the World is a lot of book with a lot of thought-provoking propositions about life and how to live it. Masquerading as a book about maps and science, it’s a manual on how to be in the world, a manual on how to live. Just as D’Ignazio and Klein’s Data Feminism turns out to be a manual on how to write a book (to say nothing of how to deal with data), and A People’s Atlas of Detroit turns out to be a manual on how to stake a claim to a place. They’re all terrific books with claims on our attention far beyond what you’d imagine they might have to offer. Read ‘em!

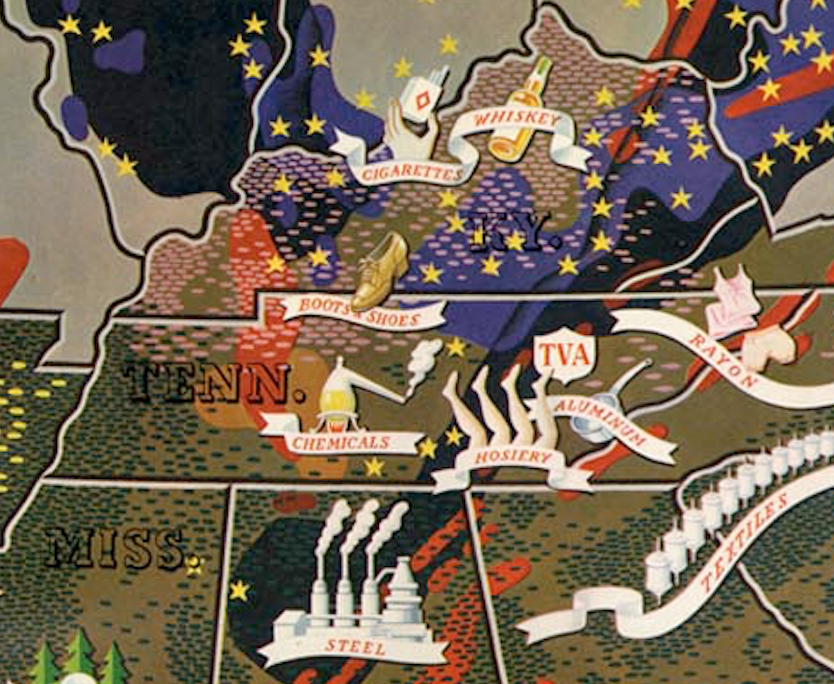

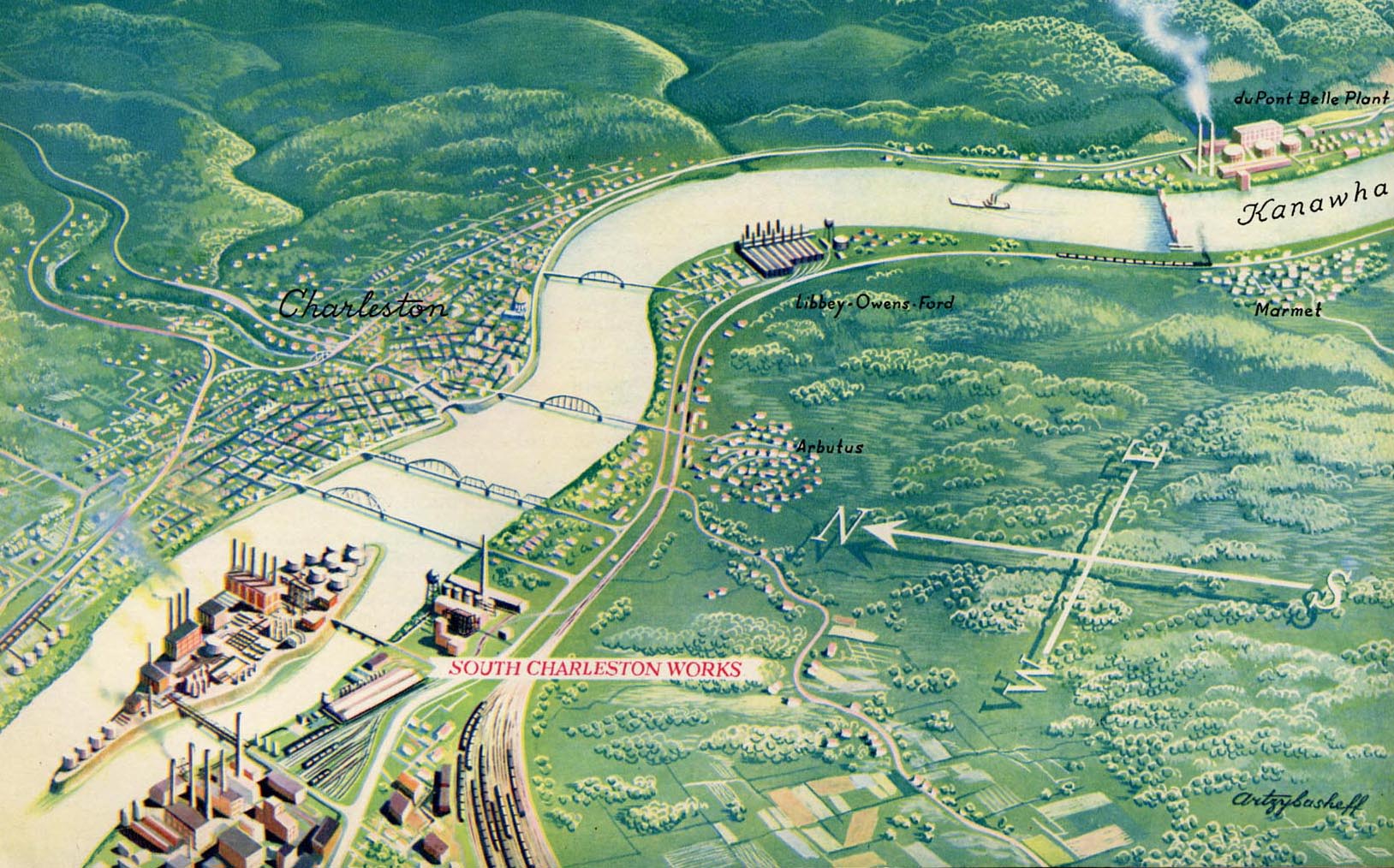

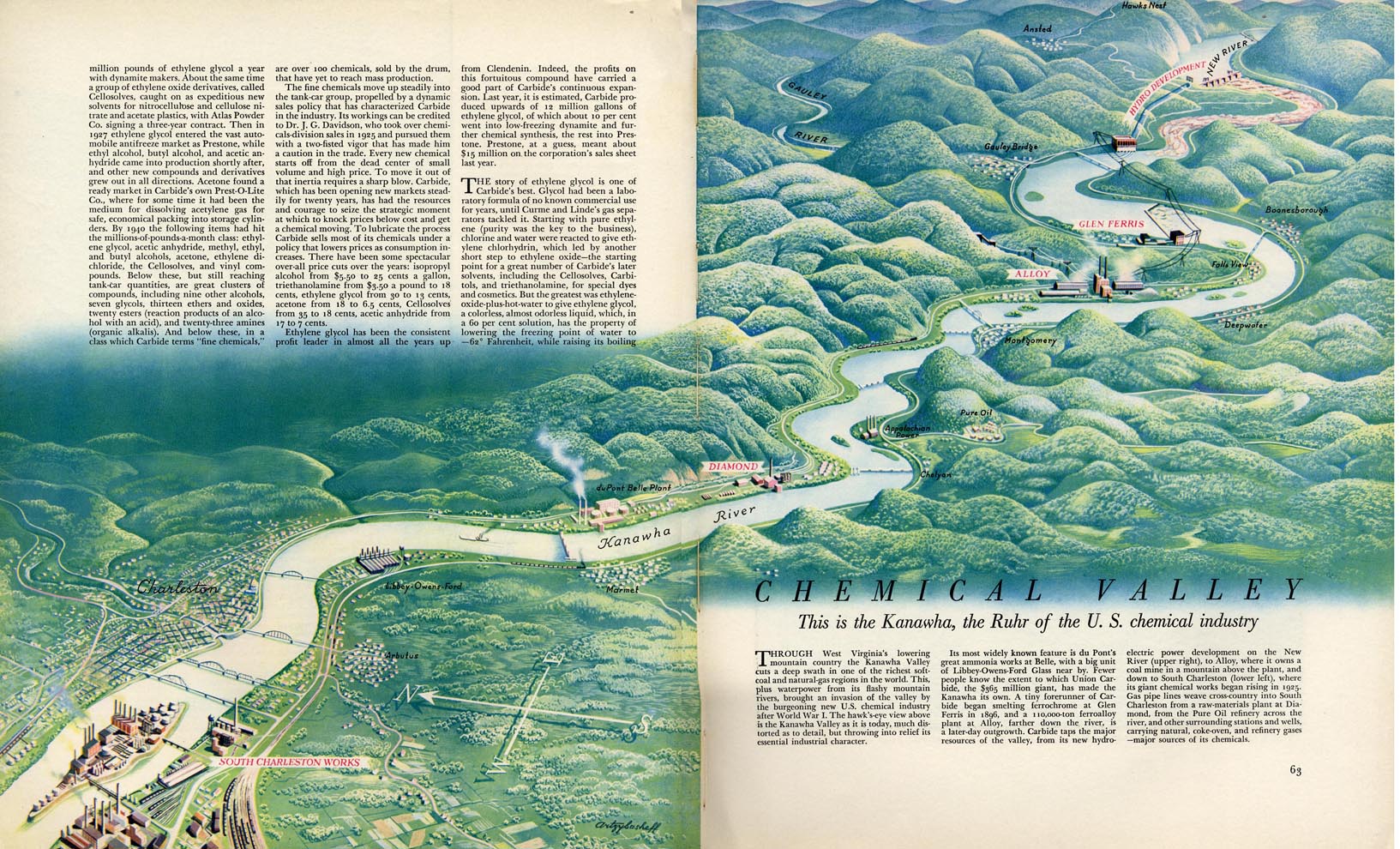

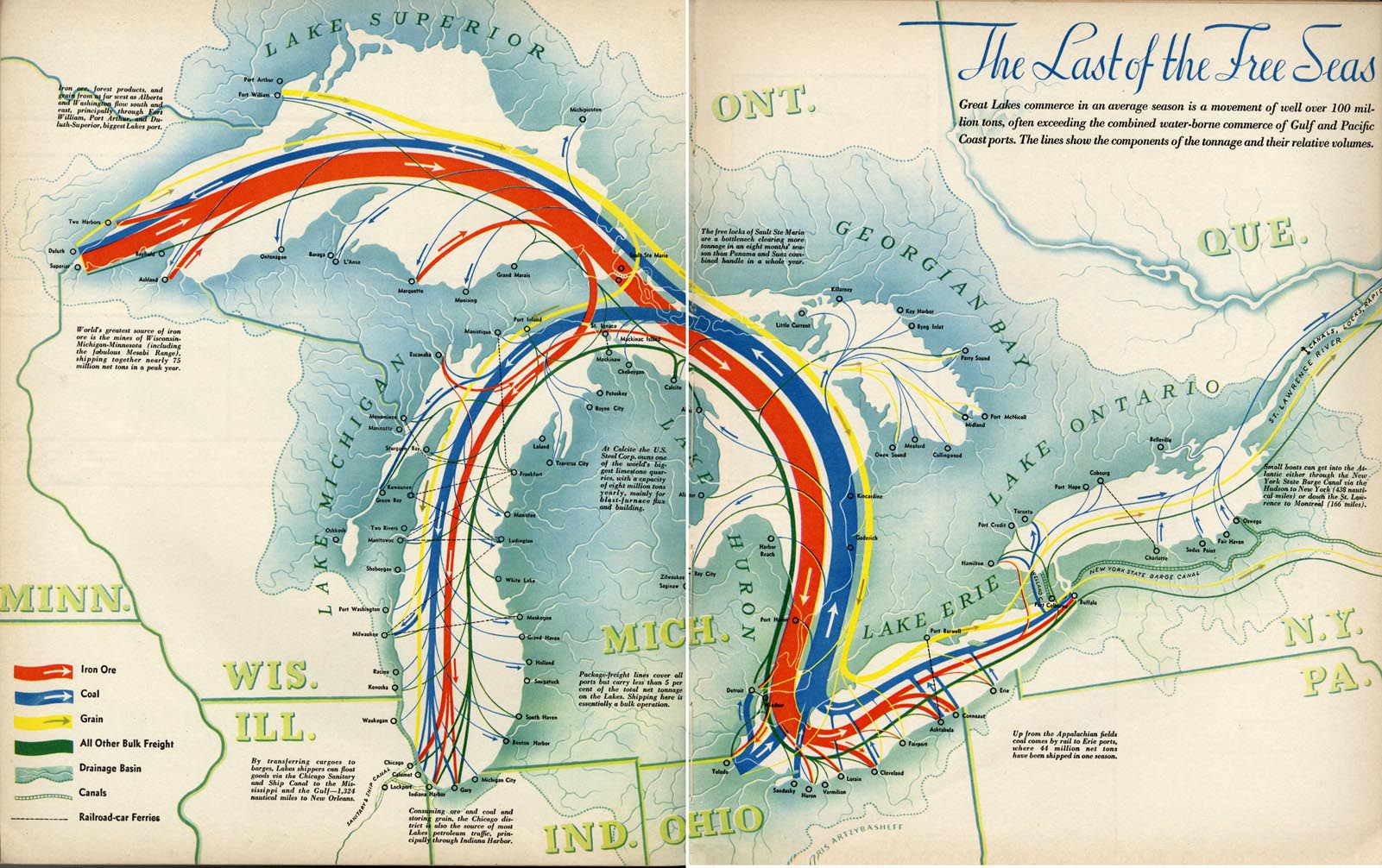

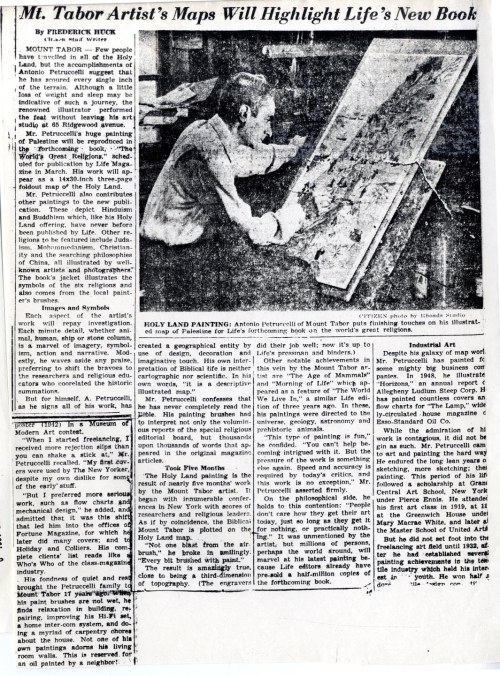

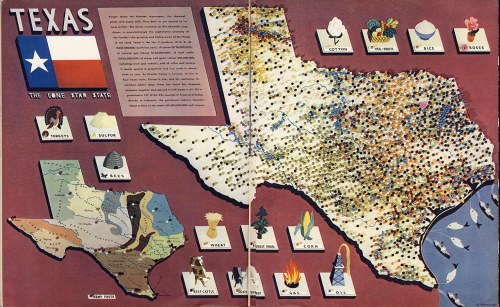

Back when Denis Wood and I were planning the 3rd edition of Making Maps, I stumbled upon a map of world tropical diseases Boris Artzybasheff created for Life Magazine (“World Map of the Major Tropical Diseases,” Life Magazine, May 1, 1944; high-resolution

Back when Denis Wood and I were planning the 3rd edition of Making Maps, I stumbled upon a map of world tropical diseases Boris Artzybasheff created for Life Magazine (“World Map of the Major Tropical Diseases,” Life Magazine, May 1, 1944; high-resolution

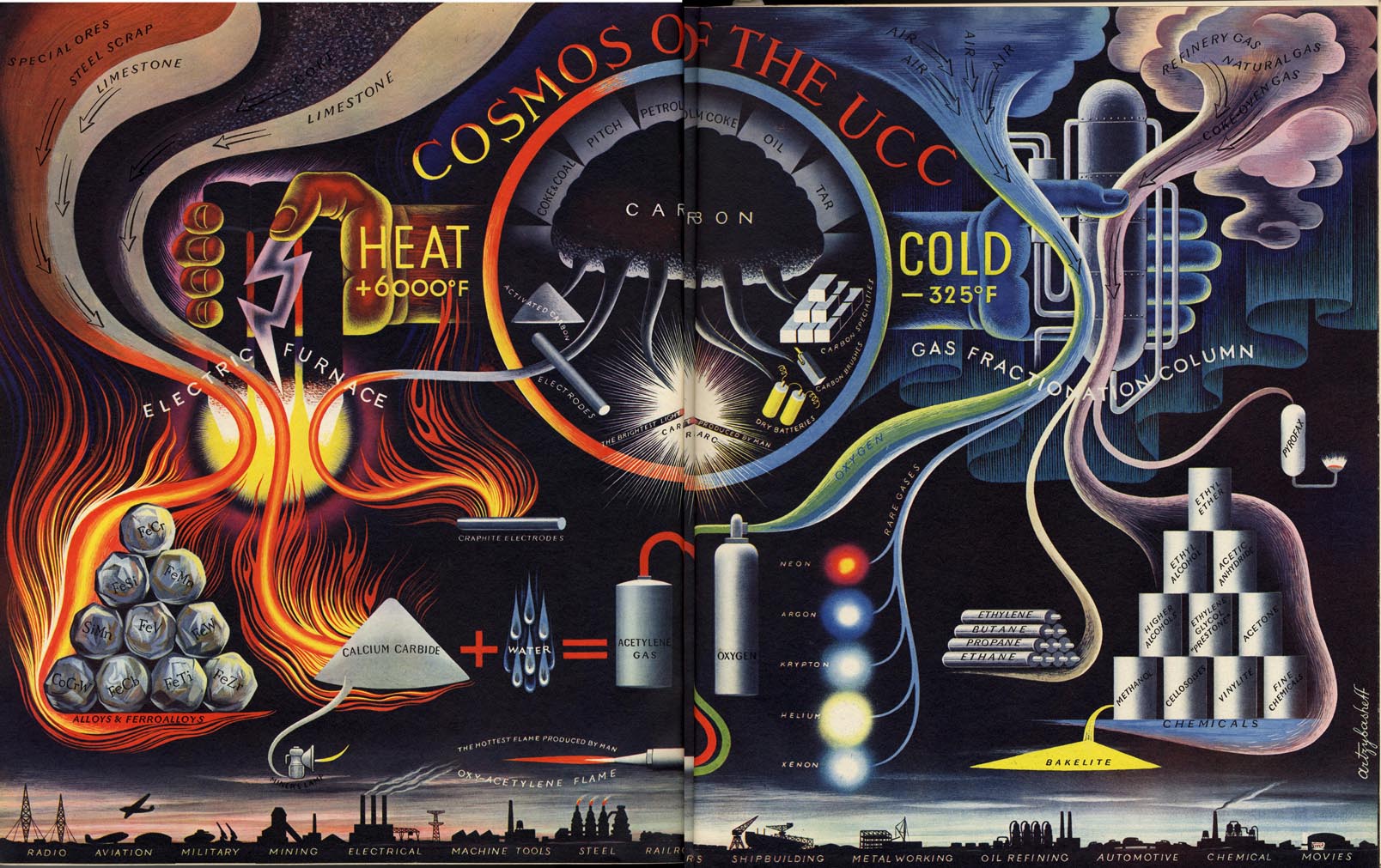

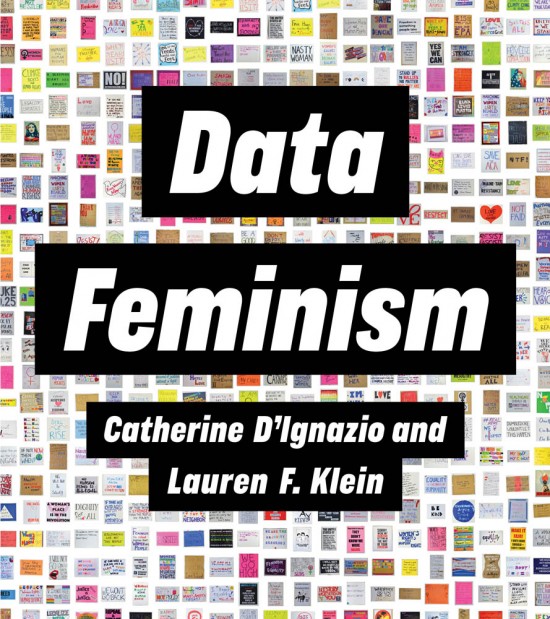

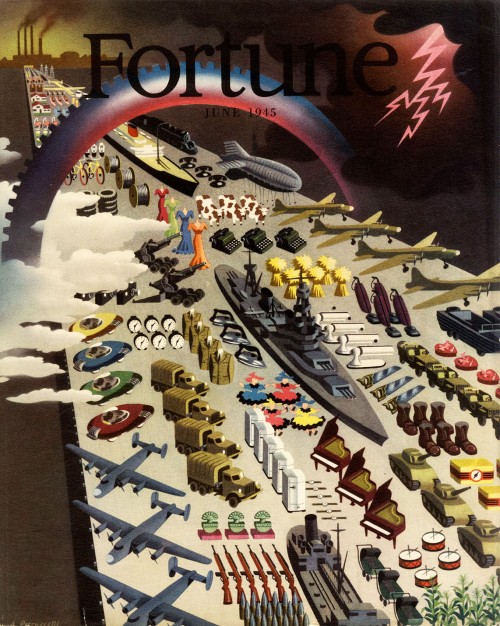

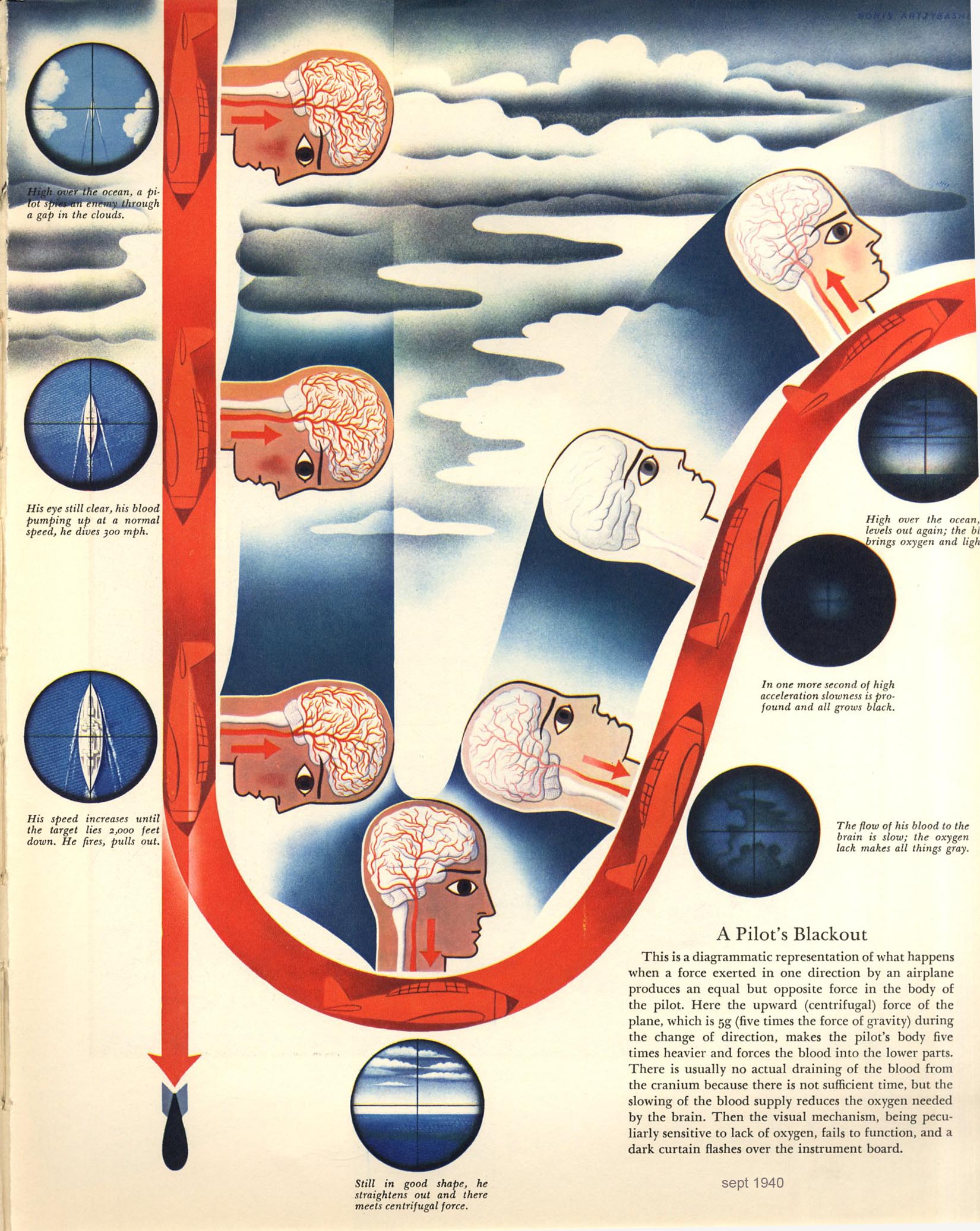

“In the late 1930s and early 1940s Artzybasheff began illustrating articles for Fortune and other popular magazines, usually with vividly drawn graphic renditions of maps or other informational diagrams. In the September, 1940 issue of Fortune magazine, for example, Artzybasheff provided a striking and colorful illustration for an article on how military pilots experience oxygen deficiencies and aeroembolism (decompression sickness or temporary blackouts attributed to nitrogen bubbles that form in the spinal fluid) when ascending rapidly to heights of 30,000 feet.” (Williams, 2007, p. 126). Diagram (left): “A Pilot’s Blackout,” from “Selection of Military Pilots: Not Every Flyer is Fit for Combat,” Fortune, September 1940, p. 81.

“In the late 1930s and early 1940s Artzybasheff began illustrating articles for Fortune and other popular magazines, usually with vividly drawn graphic renditions of maps or other informational diagrams. In the September, 1940 issue of Fortune magazine, for example, Artzybasheff provided a striking and colorful illustration for an article on how military pilots experience oxygen deficiencies and aeroembolism (decompression sickness or temporary blackouts attributed to nitrogen bubbles that form in the spinal fluid) when ascending rapidly to heights of 30,000 feet.” (Williams, 2007, p. 126). Diagram (left): “A Pilot’s Blackout,” from “Selection of Military Pilots: Not Every Flyer is Fit for Combat,” Fortune, September 1940, p. 81.

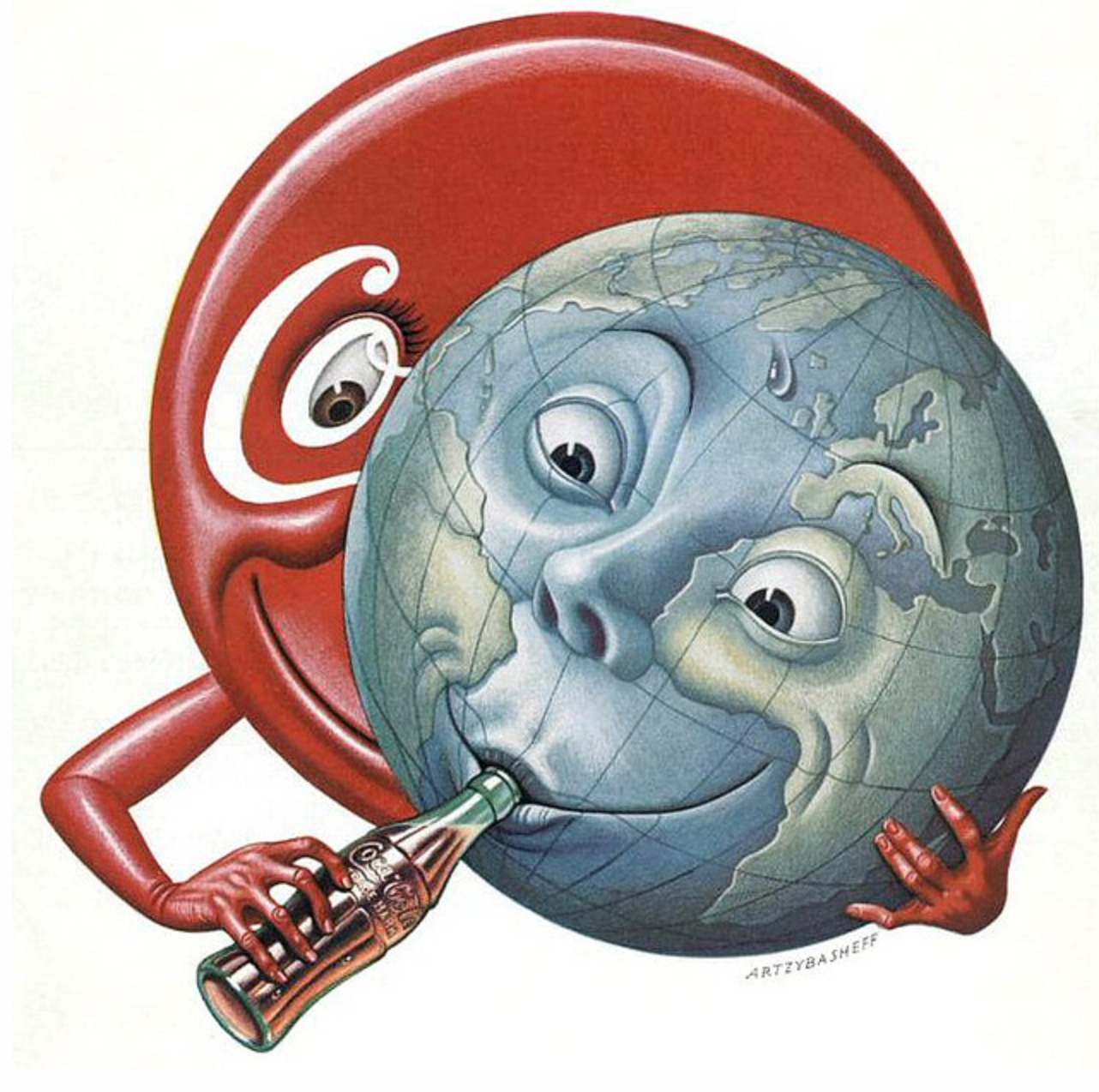

“In a 1942 letter to Artzybasheff, Boggs asks if the artist could potentially draw the head of a man on a white billiard ball, in hopes of designing a model that could show how projecting global features creates significant distortions on a flat map—in other words, flattening the nations and populations of the world is much like flattening a person’s face beyond all recognition. As he points out to Artzybasheff, ‘What I would like to get across to the ‘flat-mappers’ is that when we are looking at a flat map which includes the whole world, we are looking at a caricature which is analogous to representing the face, both sides of the head, back and top of the head, and beneath the chin all on one flat surface.” (Barney, 2011, p. 189)

“In a 1942 letter to Artzybasheff, Boggs asks if the artist could potentially draw the head of a man on a white billiard ball, in hopes of designing a model that could show how projecting global features creates significant distortions on a flat map—in other words, flattening the nations and populations of the world is much like flattening a person’s face beyond all recognition. As he points out to Artzybasheff, ‘What I would like to get across to the ‘flat-mappers’ is that when we are looking at a flat map which includes the whole world, we are looking at a caricature which is analogous to representing the face, both sides of the head, back and top of the head, and beneath the chin all on one flat surface.” (Barney, 2011, p. 189)