Cover, Making Maps, 2nd edition (Amazon | Guilford)

Krygier and Wood’s book should be used by anyone interested in the way the world looks, the way the world works, or the way the world should be. It remains the most accessible yet comprehensive guide of its kind. The second edition meets the needs and expectations of the “Google generation” of map users while remaining true to the guiding principles that govern how maps look, work, and function. The very accessible, extensively illustrated format makes the book easily usable by students at all levels, as well as those taking steps to develop expertise in cartographic design. Paul Longley, Department of Geography, University College London, United Kingdom.

Building on their solid first edition, Krygier and Wood have created a new and much richer follow-up. The second edition represents a serious reworking of subject matter and graphics. The book uses extraordinary map exemplars to address the full range of basic cartographic concepts and to demonstrate many subtle and advanced design techniques as well. Making Maps is appropriate for beginning to intermediate college cartography students and others who want to tap into the power of map creation. Addressing current social issues including map agendas, ethics, and democracy, it is the kind of book that will inspire readers and cultivate admiration for the field. James E. Meacham, Senior Research Associate and InfoGraphics Lab Director, Department of Geography, University of Oregon.

More than two years in the making, the second edition of the book Making Maps is set for printing. Copies should be available in February or March of 2011. A Korean translation (?!) is planned for 2012.

This is no weenie update: Denis and I ruthlessly reorganized and rethought every bit of content in the book. I then redesigned the entire book and spent the better part of eight months producing it. We both think it’s a much better book.

Denis and I were careful to keep the spirit of the first edition of Making Maps intact while sharpening the overall look, content, and usability of the book. The goal from the beginning was to create a map design text that was different from other map design texts – more visual, creative, critical, engaging, and focused on making maps as well as really understanding how they work. It is a synthesis of what we like most about the academic study of maps and the actual design and production of maps. It is difficult to express how complex and challenging achieving this goal has been. When I look at this new edition, it feels so easy. Why couldn’t we have just done this 8 years ago when I started on the initial edition of the book?

The 2nd edition is larger in size (now 7″ x 10″) allowing more content on each page. In a Tuftean fit of non-data-ink removal, gone are a bunch of pages that didn’t have much content (such as the overview pages near the beginning of each chapter). We did retain ample white space, since absence makes the heart fonder.

We also added new material, including many real mapped examples, yet we are dozens of pages shorter than the first edition. Our goal was a lean book – “the greatest number of ideas in the shortest time with the least ink in the smallest space” – as Tufte put it.

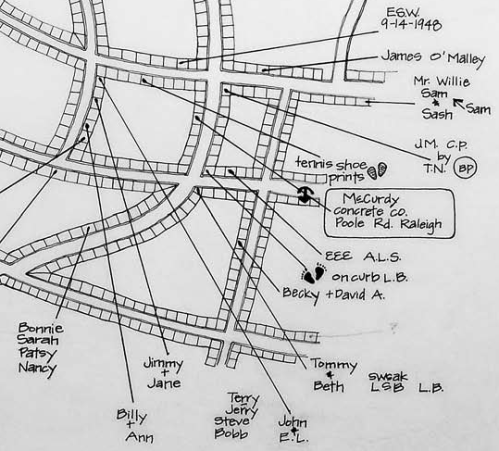

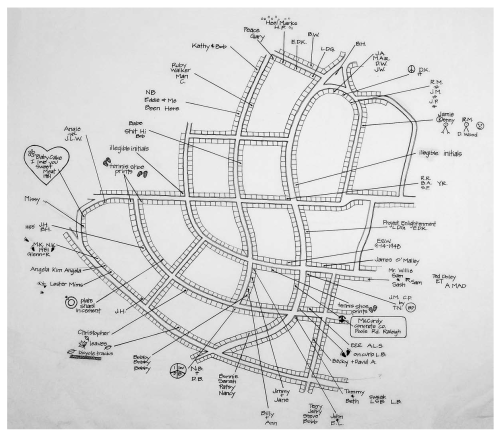

The cover initiates an expanded version of the “road connector controversy” which sets up the point of the book – you make things happen by making maps.

There is a completely new first chapter setting the context for the entire book. It introduces The Flight of Voyager map, which is annotated a dozen times over throughout the book showing how map design concepts in the text play out on an actual map:

The chapters in the book are about the same, with a new first chapter and some recast chapter names:

Introduction

1: How to Make a Map

2: What’s Your Map For?

3: Mappable Data

4: Map Making Tools

5: Geographic Framework

6: The Big Picture of Map Design

7: The Inner Workings of Map Design

8: Map Generalization and Classification

9: Map Symbolization

10: Words on Maps

11: Color on Maps

While some chapters retain a significant amount of the original edition’s material, chapters 6 and 7 were extensively revised.

A makingmaps.net blog posting “How Useful is Tufte for Making Maps?” led me to incorporate Tufte’s ideas in the book in a much more explicit manner than in the 1st edition. See, for example, the Tufte-influenced annotated Flight of Voyager map (2 page spread, chapter 6) below:

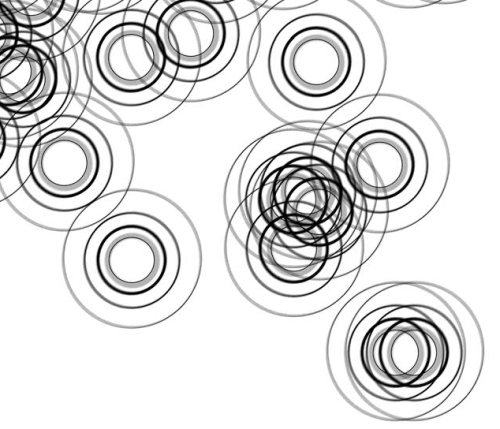

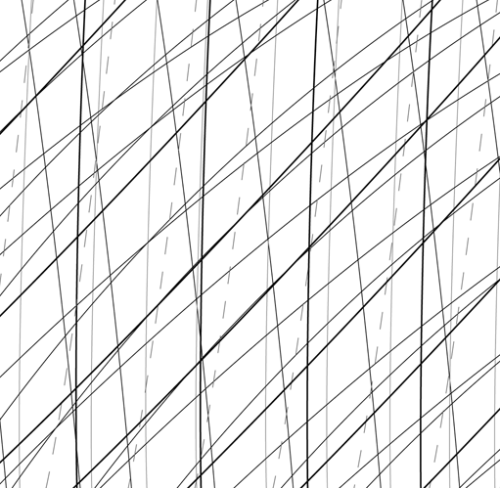

Chapter 7 was revised as “The Inner Workings of Map Design” including figure ground:

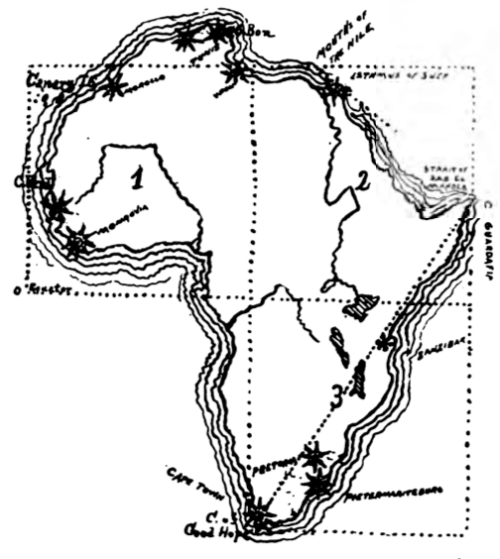

Chapter 9 on map symbols also underwent significant renovations:

•••••••••••••••

Making Making Maps … Second Edition

I am but slightly embarrassed to admit that, once again, I produced the entire book in a 6-year-old version of the now defunct Freehand MX software. My original plan was to shift to InDesign since I was redesigning the entire book, but in the end I just wanted to make the damn book rather than futzing with transferring the maps and graphics from Freehand to InDesign and learning the ins and outs of InDesign. So my plan is to eventually shift the entire book to InDesign assuming a 3rd edition sometime in the future.

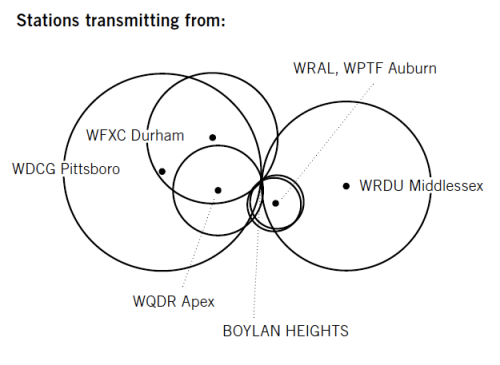

The book was produced on my 4-year-old MacBook Pro, which allowed me to work on it at home on the dining room table, at home on the table on our front porch (where Denis and I had earlier sat and pounded through the plan for the 2nd edition), at CupOJoe coffee at the end of the block, at Panera while waiting to pick up Annabelle after her morning pre-school, at soccer practice at some god-forsaken indoor soccer warehouse in the hellish outer suburbs of Columbus, in Raleigh NC whilst visiting Denis to work on the book, at the OSU recreation center with the climbing wall, at the OSU recreation center with the pool (both while waiting for kids to finish various climbey or splashy activities), at my parents house in Waukesha (Wisconsin), the Caribou Coffee in Waukesha, my in-laws in River Hills Wisconsin, and in my office at Ohio Wesleyan.

•••••••••••••••

This is really a labor of love – given the time and brain power expended on the text – and we both hope this new edition lives up to the expectations of the kind and usually enthusiastic readers of the first edition.